America's cities have never gotten along well with its network of highways in large part because nobody put very much thought into how the two would interact. Historian Lewis Mumford denounced the project in the 1950's, noting, "When the American people, through their Congress, voted a little while ago for a $26 billion highway program, the most charitable thing to assume about this action is that they hadn’t the faintest notion of what they were doing.”

The federal government had never paid very much attention to building roads, leaving much of the responsibility for it up to the states. It was not until 1912 that a nationwide road-building program was introduced, but this was limited to rural areas only. Cities were expected to cover the costs of their own infrastructure, and this bias of Washington in favor of funding rural projects was reiterated in appropriations bills in 1919, 1921, 1928, and throughout the New Deal programs. The purpose of building roads was to "bring the farmers out of the mud."

Then came the great day for the country's roads: the passage of the Federal Aid Highway Act in 1956, which established what we now know as the Eisenhower Interstate Highway System. This network of multi-lane, limited-access, high-speed roadways would link the country together more closely, facilitate commerce, allow for settlement of suburban and rural areas, and aid the national defense. According the president's highway committes, the particular design of the highways was chosen for four main reasons: (1) it could carry more vehicles at higher speeds than existing types of roads; (2) limited-access highways have fewer accidents per vehicle-mile; (3) they are cheaper to build then other types of roads of similar size; (4) they preserve “natural roadside beauty, prevent roadside blight, open up new territory for industrial commercial, and residential development, and can serve as buffers between different types of land development.”

Many planners did not anticipate the rapid outward migration from the central cities that the highways created, but the US military did, and they actively encouraged it. They felt that lower density with dispersed population centers and industry would make the country less susceptible to nuclear attack by providing the Soviets with fewer high-value targets. The spoke and wheel configuration of most cities' highways would also facilitate evacuation in the event of a strike. Nuclear armageddon is no laughing matter, but perhaps this was not the best use of resources.

Many planners did not anticipate the rapid outward migration from the central cities that the highways created, but the US military did, and they actively encouraged it. They felt that lower density with dispersed population centers and industry would make the country less susceptible to nuclear attack by providing the Soviets with fewer high-value targets. The spoke and wheel configuration of most cities' highways would also facilitate evacuation in the event of a strike. Nuclear armageddon is no laughing matter, but perhaps this was not the best use of resources.While these purposes seemed appropriate for the nation as a whole at the time, the system was utterly devoid of any attention to how highways would serve cities. There was no means for coordinating between federal planners and city administrators, and roadbeds were laid without consideration of the urban environments they cut through. The disruption from highway construction fell disproportionately on cities' low-income residents, and there were no federal appropriations for resettling displaced people. Rather than being arteries for the city, highways became barriers and outward conduits, drawing the population, commerce and life of the city out to the suburbs. Chicago's Skyway, Boston's central artery, and countless others are glaring examples of the bifurcating effect of elevated highways. But Boston especially illustrates how difficult these problems are to rectify; the Big Dig cost $22 billion just to recover 25 acres of land from the downtown's impenetrable maze.

As I often do, I will now turn to my hometown of New Haven for an instructive example about the damaging effect of highways on urban environments. Construction of the Oak Street Connector, a spur off of the interchange between I-91 and I-95 that cut right into the downtown, was tied directly to a "slum removal" program. Most of the highway was never built, but the neighborhood was still razed, leaving a swath of still unoccupied land where a neighborhood used to be.

It is worth noting that until very recently, pedestrians, cyclists, and buses were not given much thought when planning highways. New Haven's downtown is now crossed with broad one-way streets, designed to facilitate access to the interstate on-ramps. But the traffic patterns allow cars to travel too quickly through the central business district, which does not encourage commerce and makes the streets dangerous for people not in automobiles. As part of the effort to slow traffic and develop more walkable urban spaces, the city is installing bike lanes and new transit options, like streetcars. Eventually, they may even turn the one-way thoroughfares back into tight, two-way streets with curbside parking, all of which encourage people to slow and see what the city has to offer. It may be difficult to admit, but if we want to reconstruct the dense urban environments with walkable neighborhoods and reliable mass transit, we may have to sacrifice some of the speed of travel that we have become accustomed to.

'

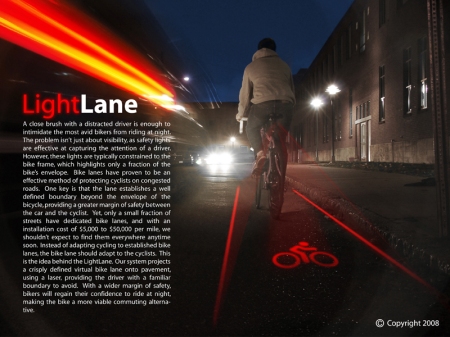

'If the feds won't build it, bring your own bike lane.

How does this all relate the the stimulus bill that the Senate is currently slicing and dicing? Well, when it comes to highways, we still do not really know what we are doing. Highway construction is attractive because of its "shovel-readiness" (a totally made up and fatuous notion), but it is still wrought with problems, especially for cities. Building roads and bridges for the sake of building provides few economic benefits, and simply makes the environment less livable, as Japan learned in the 1990's. Meanwhile, important mass transit services are being slashed just when ridership is increasing, and they have little hope of being rescued by federal cash.

We do have innovate transportation alternatives that are deserving of funding, like light rail systems, dedicated bus lanes, and congestion pricing. This is a better use of money, and will be better for the nation's cities, than road widening and re-paving, which may only exacerbate existing transit problems.

No comments:

Post a Comment